The Ambitious Dream of Terraforming: Making New Worlds Home

The concept of terraforming—the intentional, large-scale modification of a planet’s environment to render it suitable for supporting terrestrial life—stands as one of humanity’s most ambitious long-term goals. For generations, this idea has been the bedrock of science fiction, inspiring vivid depictions of a verdant, Earth-like Mars or temperate, ocean-covered Venus. While these grand visions remain firmly in the realm of speculative fantasy, contemporary planetary science and astrobiology are actively moving beyond imagination, beginning to explore genuinely practical and scientifically grounded methodologies for transforming extraterrestrial environments.

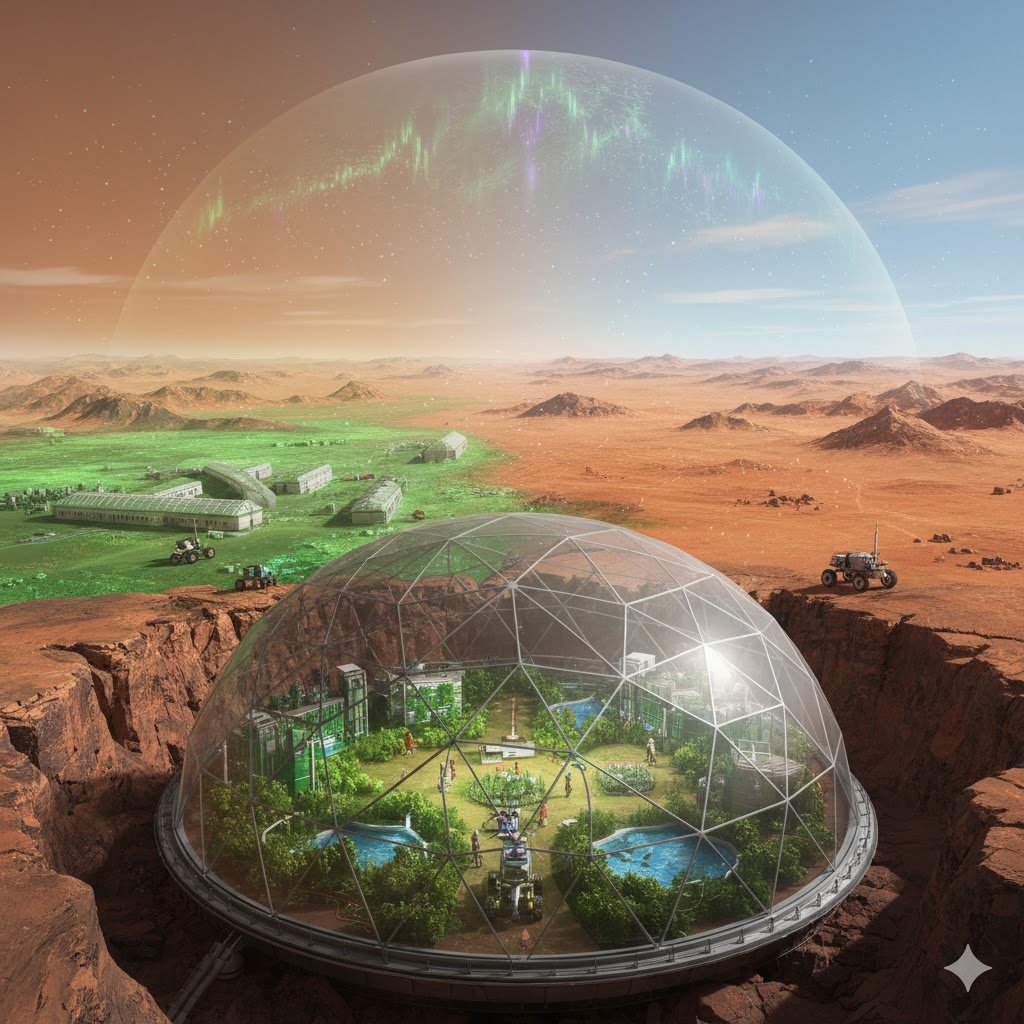

The primary target in these discussions is overwhelmingly Mars. Although we are still light-years away from creating a fully breathable atmosphere or global magnetosphere on the Red Planet, current scientific research provides realistic, incremental pathways. These initial efforts focus not on transforming the entire globe, but on creating localized, sustainable, and relatively self-contained habitats.

Realistic Stepping Stones on Mars

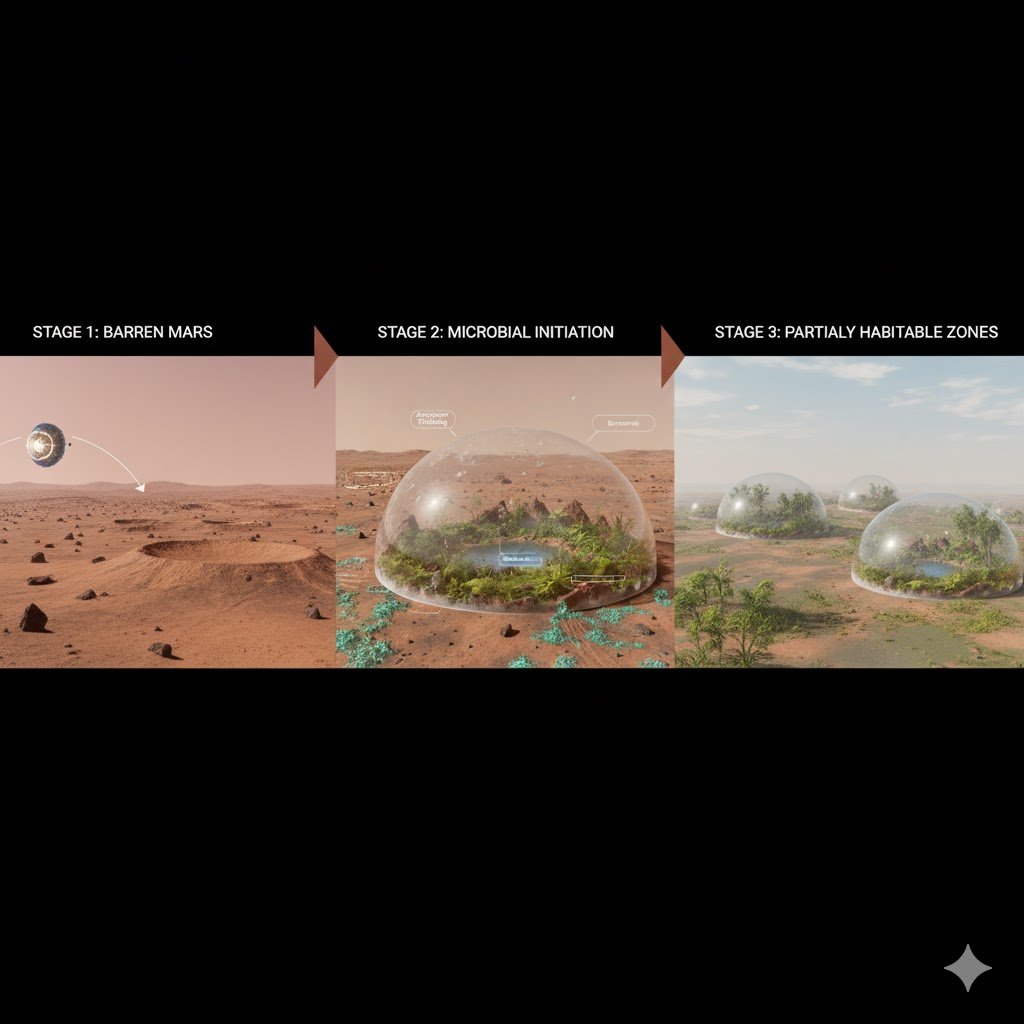

Instead of a sudden global transformation, modern research emphasizes a phased approach:

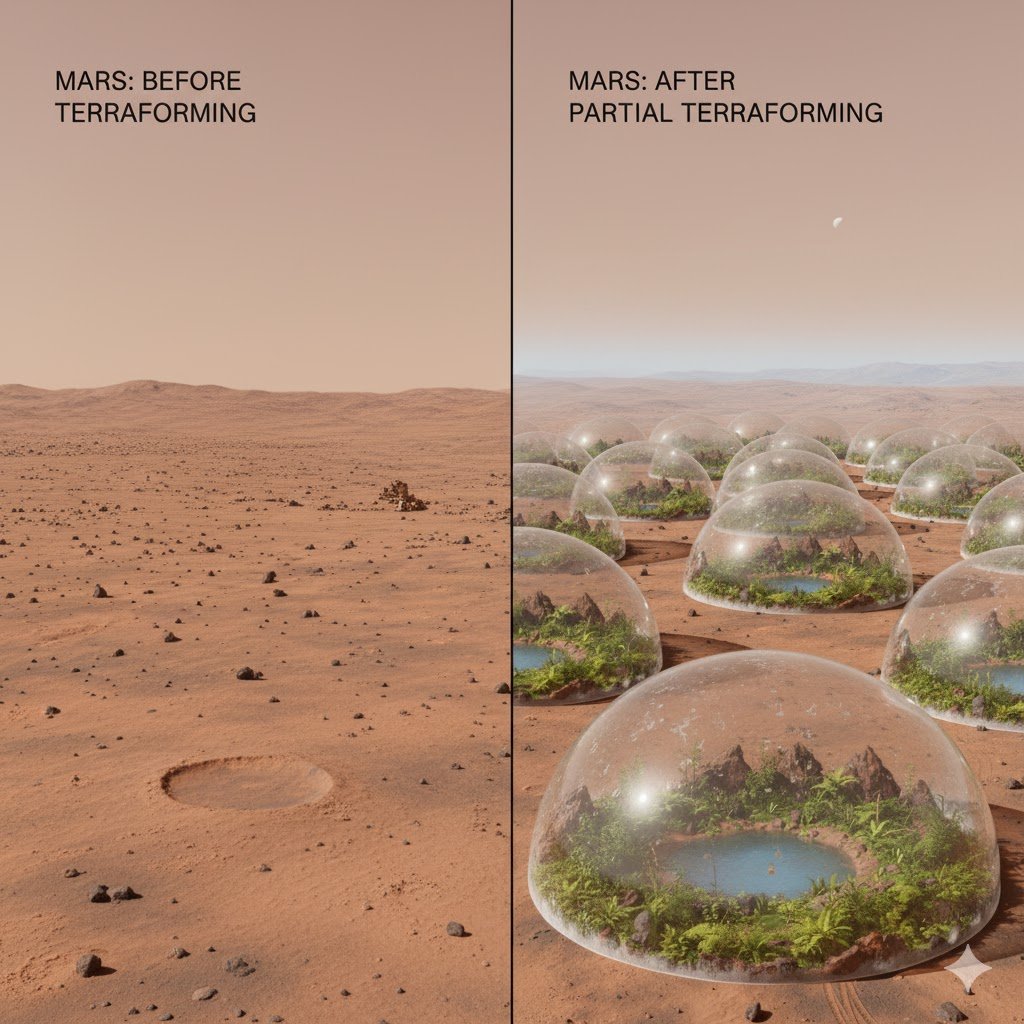

- Creating ‘Oases’ and Shelters: The most immediate and feasible approach involves building sealed, pressurized, and radiation-shielded habitats. These initial colonies—often referred to as bio-domes or Martian Oases—would be fully controlled environments, effectively importing Earth-like conditions (temperature, pressure, air composition) into a small, insulated space.

- The Atmospheric Challenge: Mars’s thin atmosphere and lack of a protective global magnetic field are major hurdles. Scientists are investigating ways to liberate frozen volatile compounds, such as carbon dioxide $\text{CO}_2$ trapped in the polar ice caps or within the regolith (soil). Releasing these gases could trigger a modest greenhouse effect, slightly raising the planet’s temperature and increasing the atmospheric pressure, albeit likely not enough for unassisted human survival outdoors.

- Biological Engineering: Introducing specific extremophile microorganisms (like certain cyanobacteria or lichens) is another key area of study. These ‘starter’ organisms could be genetically engineered to efficiently process the harsh Martian environment, releasing oxygen ($\text{O}_2$) and breaking down toxic compounds (like perchlorates) found in the Martian soil, laying the groundwork for more complex plant life in the future.

These initial, localized efforts serve as crucial stepping stones. They represent a bridge between purely theoretical science fiction and the reality of interplanetary settlement. By mastering these smaller transformations, humanity will acquire the essential knowledge and technology needed to potentially scale up to the truly daunting task of achieving full, planet-wide terraforming.

The “Glitter” Method: Warming Mars with Nanoparticle Dust

One of the most innovative and achievable proposals for initiating the terraforming process on Mars is the strategic deployment of engineered metallic nanoparticles—a technique often colloquially referred to as the “glitter” method. This approach offers a practical, scaled-down solution to the planet’s immense coldness, sidestepping the colossal resource and energy demands of older, more conventional warming schemes.

How the Nanoparticle Greenhouse Works

The core mechanism involves releasing vast quantities of ultra-fine, specially designed metallic dust into the Martian atmosphere. These particles, typically measured in nanometers, are engineered to optimize their interaction with light.

- Heat Absorption and Scattering: Once suspended high above the surface, these tiny structures act as an extremely efficient thermal blanket. They are designed to absorb incoming solar radiation—particularly in the infrared spectrum—and then re-radiate that heat back toward the surface. Concurrently, they scatter visible light, reducing the amount of sunlight reflected back into space and effectively trapping thermal energy.

- Targeted Warming: Scientists estimate that this atmospheric manipulation could lead to a significant temperature rise of several tens of degrees Celsius over a relatively short period, potentially a single decade. This targeted warming effect would be an essential prerequisite for any subsequent large-scale biological or environmental transformation.

Practicality and Control: A New Era of Planetary Engineering

The nanoparticle method is favored by many researchers for its practicality and inherent advantages over proposals that relied on the massive importation or industrial manufacture of traditional greenhouse gases.

- Resource Availability: Crucially, the materials needed—such as iron and aluminum—are abundant within the Martian regolith (soil). This means the process can be accomplished using in-situ resources, eliminating the prohibitively high cost and logistical nightmare of transporting materials from Earth.

- Controllable and Reversible: Unlike permanent atmospheric changes, the density and composition of the nanoparticle layer can be meticulously managed. If experiments yield undesirable results, the scattering layer can be allowed to dissipate naturally, giving scientists an unprecedented degree of localized control and reversibility over planetary climate experiments.

The Essential First Step: Unleashing Liquid Water

While this dust-based greenhouse effect would not immediately render the air breathable for humans, the temperature increase is sufficient to achieve the most critical step for Martian colonization: melting frozen water.

Raising the mean surface temperature allows the copious quantities of water ice locked beneath the surface and at the poles to become liquid. The presence of liquid water is the single most important factor for agriculture, life support, and creating a stable, high-pressure environment for initial colonies. By enabling the hydrological cycle, the “glitter” method provides a practical, incremental stepping stone toward transforming a cold desert into a potential cradle for terrestrial life.

Silica Aerogel Domes: Creating Localized Martian Ecosystems

Moving away from the monumental task of global terraforming, a more immediate and practical proposal focuses on creating small, controlled habitats using a revolutionary material: silica aerogel. Often referred to as “frozen smoke” due to its lightness and appearance, this translucent, ultra-low-density substance allows researchers to engineer self-contained, habitable zones right on the Martian surface.

The Mechanism of the Aerogel Dome

The strength of the silica aerogel concept lies in its remarkable thermal and optical properties:

- Solar Greenhouse Effect: A sheet of aerogel, only two to three centimeters thick, acts as an incredibly efficient thermal insulator. It is nearly transparent to visible light, allowing the full spectrum of sunlight through to the ground or to plants beneath it—crucial for photosynthesis.

- Heat Trapping: Simultaneously, it is an excellent infrared absorber and insulator. Once sunlight hits the ground and re-radiates heat back as infrared energy, the aerogel layer effectively traps that warmth, preventing it from escaping into the frigid Martian atmosphere. This passive heating mechanism can elevate temperatures underneath the layer to above the freezing point of water ($0^\circ\text{C}$), even in the cold Martian environment.

- Radiation Shielding: Beyond temperature regulation, the dense, porous structure of the aerogel is highly effective at blocking the constant stream of dangerous ultraviolet (UV) radiation that bombards the surface of Mars due to its thin atmosphere and lack of an ozone layer. This dual function—warming and shielding—makes it an ideal material for protecting early life.

Scaling Up Habitability

This approach is highly incremental and scalable. Initially, small patches or domed structures can be deployed to house microbial experiments or test plant growth. Over time, these greenhouse zones could be expanded to cover much larger areas, effectively merging engineering and ecology.

The silica aerogel dome strategy represents a pragmatic method for achieving in-situ habitability. It allows scientists to conduct practical experiments on survival, plant growth, and ecosystem development without requiring any immediate, large-scale alterations to the entire Martian atmosphere. It offers a sustainable pathway to establishing a Martian base and paves the way for future, larger-scale colonization efforts.

Engineered Biology: The Power of Life in Terraforming

The future of planetary transformation may not rely solely on advanced technology and colossal engineering projects, but also on the quiet, yet transformative power of engineered biology. This approach leverages self-sustaining microbial and botanical systems to perform complex ecological tasks, dramatically reducing the need for constant human intervention over long timescales.

Microbial Engineers: Modifying the Environment

The smallest organisms could be the most impactful agents of change on Mars.

- Atmospheric and Soil Modification: Scientists are exploring the use of specially designed extremophiles—microbes genetically engineered to thrive in the harsh Martian environment. Their primary roles would include:

- Oxygen Production: Certain cyanobacteria are highly efficient at photosynthesis, capable of taking in Martian $\text{CO}_2$ and releasing breathable $\text{O}_2$. Even a slow, initial production could begin the process of thickening the atmosphere.

- Soil Detoxification: The Martian regolith contains high levels of toxic perchlorates. Engineered microbes could be tasked with breaking down these compounds, making the soil chemically suitable (or fertile) for supporting complex plant life later on.

- Nitrogen Fixation: Introducing bacteria capable of nitrogen fixation would pull nitrogen from the atmosphere or soil and convert it into biologically useful forms, which is essential for plant growth and sustaining a more robust ecosystem.

Bioconstruction: Growing Habitats

Beyond chemistry, biology can aid in physical construction, offering a sustainable alternative to traditional building materials:

- Self-Growing Materials: Organisms similar to lichens or specialized fungi could be utilized to “grow” infrastructure. These organisms possess the ability to colonize and secrete binding agents that aggregate the loose, fine-grained Martian dust (regolith) into strong, structurally sound materials. Essentially, they could turn dust into usable biocrete blocks or other building structures, allowing colonists to create pressurized habitats and radiation shelters with minimal imported material.

- Ecological Pioneers: Research into resilient organisms like certain mosses and cyanobacteria has already demonstrated their ability to survive and even photosynthesize under low-pressure, high-radiation conditions in simulated Martian environments. These organisms are the pioneer species—the foundational layer of a slow ecological succession that hints at the eventual possibility of establishing small, functional terrestrial ecosystems on another planet.

By harnessing these self-regulating, reproducing biological systems, terraforming efforts become less about maintaining complex machinery and more about nurturing a slowly evolving, self-replicating ecological engine, potentially leading to a more sustainable and successful long-term transformation of Mars.

Magnetic Shielding: Protecting Mars’s Future Atmosphere

The single greatest long-term obstacle to transforming Mars into a habitable world isn’t its cold temperature or thin air, but the fact that it can’t hold an atmosphere. The planet lacks the powerful, global magnetic field (a magnetosphere) that shields Earth, which means the solar wind—a constant stream of high-energy charged particles from the Sun—is free to relentlessly erode and strip away any gases introduced into the Martian atmosphere.

The Proposal: The L1 Magnetic Dipole

To overcome this fundamental challenge, scientists have put forth a bold, technically demanding, but potentially game-changing solution: deploying an artificial magnetic shield.

- Location: This shield wouldn’t be on the planet itself, but positioned in space at Mars’s L1 Lagrangian point. The L1 point is one of five gravitationally stable locations in the Sun-Mars system, situated directly between the two bodies. Placing the shield here would allow it to remain stationary relative to Mars without expending continuous energy for orbital maintenance.

- Mechanism: The proposed shield would be a colossal, powerful magnetic dipole (a structure generating a huge magnetic field) creating a protective bubble. This magnetic field would act as an immense, invisible umbrella, deflecting the solar wind away from Mars, much like Earth’s natural magnetosphere does.

A Key Enabler for Long-Term Habitability

Implementing this shield wouldn’t create an atmosphere overnight, but it would fundamentally change the rules of the terraforming game.

- Atmospheric Retention: By eliminating the primary mechanism of atmospheric loss, the shield would allow any gases released onto Mars (whether by nanoparticle warming, microbial action, or other means) to accumulate naturally. Over a time frame of centuries, the atmosphere could gradually thicken and become dense enough to provide better insulation and raise surface pressure.

- Radiation Protection: Furthermore, by deflecting the solar wind, the shield would significantly reduce the amount of cosmic and solar radiation reaching the surface. This is critical for protecting early human settlements and fragile Martian ecosystems.

While the engineering required to build, power, and maintain such a massive device at the L1 point is currently beyond our capabilities, this concept is viewed as the key enabler—a necessary technological leap that would make all other large-scale terraforming proposals for Mars viable in the long run.

Stepwise Terraforming: A Realistic, Incremental Roadmap to a New Earth

The monumental goal of transforming an entire world, like Mars, is not a task that can be accomplished with a single, sweeping technological intervention. Instead, scientists and engineers envision a pragmatic and stepwise roadmap, where each phase builds upon the success of the last, gradually accumulating changes over long timescales. This is an incremental strategy that maximizes efficiency and minimizes risk.

Phase 1: Localized Warming and Shelter

The initial focus is on establishing foundational conditions necessary for life, prioritizing safety and immediate utility:

- Creating Thermal Oases: The process begins with localized warming using highly controlled methods. This includes deploying silica aerogel domes to create protected, pressurized, and heat-trapping greenhouses, and perhaps initiating regional warming via nanoparticle dust dispersal. These initial zones would allow for the presence of liquid water and shield early colonies from radiation.

- Proof of Concept: These isolated habitats serve as crucial testing grounds for biological and engineering systems before any larger deployment.

Phase 2: Atmospheric Kickstarting

Once local conditions are stable, the next challenge is to address the thin, cold atmosphere:

- Releasing Volatiles: Targeted efforts would focus on liberating frozen gases, primarily carbon dioxide ($\text{CO}_2$), currently locked in Mars’s polar ice caps or potentially within underground clathrate reservoirs. This release is intended to initiate a modest runaway greenhouse effect, thickening the atmosphere and slightly raising the mean global temperature.

- Pressure Increase: The primary goal of this phase is to increase the atmospheric pressure enough to slow down the sublimation of water ice, making it easier to sustain liquid water on the surface, even if the atmosphere remains unbreathable.

Phase 3: The Biological Revolution

With slightly warmer temperatures and a denser atmosphere, biological agents are introduced as the planet’s self-replicating workforce:

- Introducing Microbial Pioneers: Engineered microbes, such as specialized cyanobacteria, would be deployed across the newly established habitable zones. These hardy organisms are tasked with beginning the slow, centuries-long process of oxygen production and breaking down toxic compounds in the Martian soil (regolith).

- Ecological Foundation: Lichen-like organisms would simultaneously begin the process of bioconstruction, binding the loose dust into stable, fertile ground capable of supporting more complex flora.

Phase 4: Expansion and Ecosystem Development

As the planet slowly responds to these initial changes, the focus shifts to expanding the scope of habitability:

- Expanding Habitable Zones: Protected, pressurized colonies would expand outward, gradually linking up the small aerogel greenhouse zones into larger, enclosed environments.

- Complex Ecosystems: Hardy plants and genetically engineered flora, capable of surviving the evolving Martian environment, would be introduced to further accelerate $\text{O}_2$ production and build complex, stable terrestrial ecosystems and food chains.

Phase 5: Long-Term Global Stability

The final, critical phase involves securing the atmosphere for millennia to come, ensuring the entire project is not undone by solar forces:

- Magnetic Shield Deployment: The ultimate long-term technology—the L1 Magnetic Dipole Shield—would need to be deployed at the Sun-Mars Lagrangian point. This essential piece of megastructure engineering would deflect the solar wind, allowing the gradually thickening atmosphere to be retained permanently. This makes the overall transformation sustainable and marks the final step toward true, long-term habitability.

Challenges and Limitations: The Sober Reality of Planetary Engineering

Despite the inspiring vision and innovative proposals for terraforming, the process is fraught with significant technical, resource, and ethical challenges that must be addressed before global transformation can become a reality. These hurdles necessitate a realistic, cautious, and long-term approach.

1. Insufficient Planetary Resources: The $\text{CO}_2$ Problem

One of the most critical recent discoveries casting doubt on large-scale terraforming is the lack of indigenous resources needed to truly kickstart a stable, warm atmosphere.

- Limited Carbon Dioxide Inventory: Recent NASA-sponsored studies have confirmed that Mars does not possess enough accessible $\text{CO}_2$ (carbon dioxide) in its polar caps, surface regolith, or shallow minerals to create a dense atmosphere. Mobilizing all currently known accessible $\text{CO}_2$ sources would only result in an atmospheric pressure far below the minimum required to keep liquid water stable or prevent humans from needing pressure suits.

- Alternative Importation: This severe resource deficit implies that any plan relying solely on $\text{CO}_2$ must be abandoned. Instead, highly potent, non-indigenous super-greenhouse gases (like fluorinated compounds or methane) would have to be continually manufactured or imported on an absolutely enormous scale—a prohibitive engineering task.

2. Time Scales and Commitment

Terraforming is not an instant process; it demands commitment spanning generations and even millennia:

- Centuries, Not Decades: Warming the planet, accumulating enough atmospheric mass, and creating a global ecosystem will not happen over a human lifetime. Even under optimistic projections, the required ecological and atmospheric changes would take decades to centuries, while the recovery of a stable atmosphere (even with a magnetic shield) could stretch into millennia.

- Intergenerational Commitment: Such long time frames require unprecedented political, economic, and cultural stability on Earth to maintain the effort across countless generations.

3. Profound Ethical Considerations: Planetary Protection

Perhaps the most sensitive challenge lies in the philosophical and moral realm, primarily concerning planetary protection:

- Threat to Native Life: The core ethical dilemma is the high probability that introducing highly competitive, robust Earth life (forward contamination) would inevitably threaten or completely exterminate any potential native Martian life forms, especially microbes (extremophiles) that may be living beneath the surface. For many scientists, the existence of an independent biology, even microbial, must take precedence over human expansion.

- Erasing Planetary History: Large-scale transformation, particularly methods involving deep mining or nuclear release, risks destroying invaluable geological and historical evidence of Mars’s past and any record of its biological evolution.

4. Technical Risks and Unknowns

Even with innovative technologies, the engineering risks are enormous:

- Shield Failure and Maintenance: Building and perpetually maintaining the colossal L1 Magnetic Shield—a technology far beyond current engineering capability—poses immense challenges. A shield failure could result in the rapid loss of years or centuries of atmospheric build-up.

- Nanoparticle Fallout Toxicity: While the “glitter” method promises warming, the long-term environmental fate of engineered nanoparticle fallout is largely unknown. On Earth, nanoparticles can be toxic, accumulate in biological tissues, and impact food chains. Deploying them globally on Mars could unintentionally poison the very ecosystems we intend to create.

- Infrastructure Resilience: The sheer scale of infrastructure required, from massive aerogel domes to power generation facilities, requires unprecedented resilience against Martian dust storms, radiation, and meteorite impacts.

Taken together, these limitations confirm that a successful, full-scale terraforming of Mars remains firmly in the realm of future possibility, contingent on massive technological breakthroughs and profound shifts in global commitment.

Conclusion: Terraforming—From Fiction to Feasibility

The concept of terraforming has successfully transitioned from the realm of pure science fiction into a speculative yet serious scientific field of study. While the grand vision of transforming an entire world like Mars into a second Earth remains a distant, long-term goal—a project spanning centuries—current research focuses on achievable, incremental steps that leverage cutting-edge technology.

The New Focus: Localized Transformation

Modern approaches recognize the immense difficulty of immediately altering a planet’s global environment. Instead, the emphasis has shifted dramatically toward localized, controlled transformation using highly advanced interdisciplinary methods:

- Physics and Materials Science: Innovations like silica aerogel domes provide immediate, small-scale habitat protection by passively trapping heat and blocking harmful radiation. Similarly, proposals for nanoparticle warming offer a controllable, regional method for slightly raising the surface temperature, a necessary first step for melting water.

- Synthetic Biology and Ecology: The use of engineered microbes and resilient pioneer species (like lichens and mosses) offers a biological pathway to gradually modify the atmosphere, detoxify the soil, and begin the production of essential oxygen. This leverages self-sustaining biological systems to reduce reliance on complex mechanical infrastructure.

- Astro-Engineering: Long-term solutions, such as the deployment of a magnetic shield at Mars’s L1 point, address the core planetary deficit—the lack of a magnetosphere—providing the necessary conditions for any generated atmosphere to be retained over geological time.

These carefully planned, stepped efforts could realistically allow humans to establish small, sustainable habitats and research outposts on Mars. More importantly, the required innovations are yielding invaluable insights into planetary science, environmental resilience, and synthetic biology, knowledge that is crucial not only for future off-world colonization but also for planetary stewardship here on Earth. The journey to a self-sufficient human presence on Mars is thus paved with small, achievable scientific victories that make the impossible seem merely improbable.

FAQ on Terraforming

Q1: What exactly is terraforming?

Terraforming is the deliberate, large-scale process of modifying an entire planetary environment to make it capable of sustaining Earth-like life, particularly human beings, without extensive life-support systems. This typically involves a multi-pronged approach: significantly warming the planet, thickening its atmosphere, establishing a global water cycle, and successfully introducing resilient ecosystems.

Q2: Which planets are considered candidates for terraforming?

Mars is overwhelmingly the primary focus. It’s considered the best candidate due to its relatively short day/night cycle (about 24.6 hours), the presence of vast reserves of frozen water, and a geological history that suggests it once held a much thicker atmosphere. While planets like Venus or icy moons like Europa and Titan are theoretically considered, they present exponentially greater technological challenges (e.g., Venus requires removing a crushing $\text{CO}_2$ atmosphere and cooling the surface from over $450^\circ\text{C}$).

Q3: How realistic is the terraforming of Mars with current technology?

Full-scale global terraforming is not currently possible. We lack the capacity to execute the large-scale atmospheric and magnetic engineering required. However, the scientific community is making significant strides in developing localized and incremental approaches. These methods—like building silica aerogel domes, employing nanoparticle warming, and utilizing engineered microbes—are realistic and could create small, sustainable, habitable zones for human colonies within the next few decades.

Q4: What is the “nanoparticle” or “glitter” method?

This is a proposal involving the deployment of engineered metallic nanoparticles (ultra-fine dust) into the Martian atmosphere. These particles are designed to act as a highly efficient atmospheric blanket. They absorb incoming sunlight and trap the thermal energy trying to escape, thus initiating a greenhouse effect that could raise surface temperatures by tens of degrees. This crucial warming is intended to melt frozen water, a critical first step toward habitability.

Q5: Can Earth life survive on the surface of Mars today?

Generally, no. Unprotected Earth life would struggle immensely due to Mars’s hostile conditions: extreme cold, an ultra-thin atmosphere (less than 1% of Earth’s pressure), lethal levels of solar and cosmic radiation, and soil that contains toxic perchlorates. However, certain extremophile microbes and specially engineered mosses or cyanobacteria have demonstrated limited resilience in simulated Martian environments, indicating that life can potentially be sustained in controlled or shielded local habitats.

Q6: What are the most significant challenges to terraforming Mars?

The major obstacles are multifaceted:

- Resource Scarcity: Mars likely lacks enough readily accessible $\text{CO}_2$ to naturally create a dense, functional atmosphere.

- Protracted Time Scales: Atmospheric and ecological changes require commitment spanning decades to centuries, far exceeding typical human planning horizons.

- Ethical Dilemma: There’s a serious moral concern regarding the contamination of the planet and the potential destruction of any native Martian microbial life forms.

- Unprecedented Technical Risks: Deploying and maintaining colossal engineering projects, such as the L1 magnetic shield, or dealing with the unknown long-term effects of nanoparticle fallout are massive technological gambles.

Q7: Would successful terraforming make Mars breathable for humans right away?

No, not at all. The initial phases focus entirely on warming the environment and increasing atmospheric pressure to stabilize liquid water. Achieving a sufficient level of oxygen ($\text{O}_2$) saturation (around $13\%$ to $15\%$ of the atmosphere) that allows humans to breathe without life support is a goal that would take many centuries of continuous biological activity (i.e., plant and microbial photosynthesis) and strong atmospheric retention.

Q8: How would an artificial magnetic shield protect Mars?

Mars’s iron core is geologically inactive, meaning it has no natural, protective magnetosphere. The lack of this field allows the Sun’s constant stream of charged particles (solar wind) to violently strip away any existing or introduced atmospheric gases. An artificial magnetic dipole placed at the Sun-Mars L1 Lagrangian point would generate a powerful, deflecting magnetic field. This shield would halt the atmospheric erosion, allowing gases to accumulate slowly and thicken the atmosphere over time.

Q9: Why is full terraforming still often described as “science fiction”?

While the mechanisms proposed are scientifically sound, the term “science fiction” still applies to the full-scale transformation because the required scale, resources, and engineering capacity are currently far beyond human capability. The necessary technologies (e.g., L1 magnetic shield, planetary-scale greenhouse gas delivery) do not yet exist, and the project’s time commitment and ethical stakes place it outside the scope of near-term, feasible projects. Current research focuses on the achievable, incremental controlled experiments that move the concept closer to engineering reality.