For millennia, the cosmos—that vast, enigmatic final frontier—has captivated human imagination, beckoning us with its profound mysteries and limitless potential. Yet, as humanity’s presence in Earth’s orbit steadily intensifies, driven by an ever-growing dependence on communication and observation satellites, international space stations, and ambitious exploratory missions, a silent and insidious danger is accumulating: space debris.

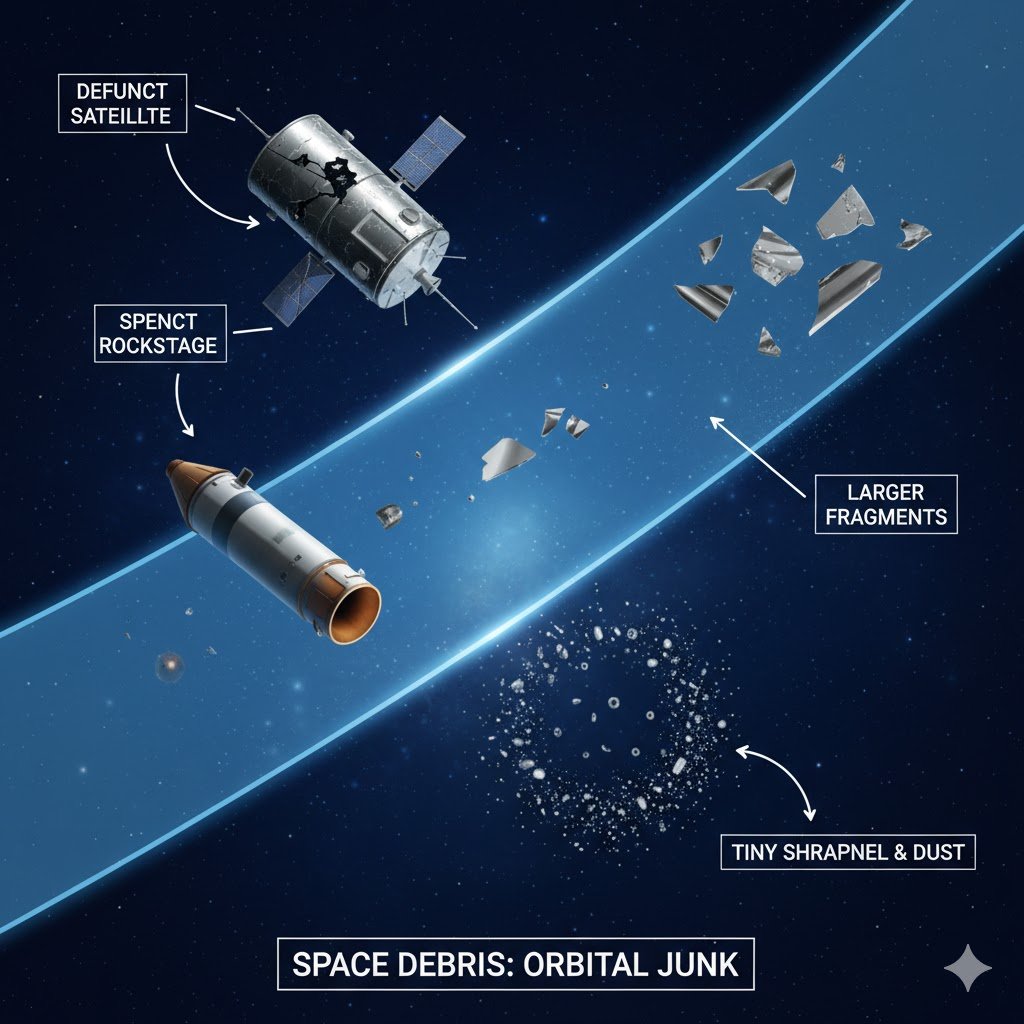

This burgeoning environmental concern, frequently referred to as “space junk,” is no longer a peripheral issue; it is fast evolving into a critical threat. Essentially, space debris comprises defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, fragments from collisions, and small flecks of paint—all orbiting at extremely high velocities.

This orbital clutter poses a dual danger:

- Threat to Active Assets: Even tiny, untraceable pieces of debris can travel at speeds exceeding $27,000 \text{ km/h}$, possessing enough kinetic energy to catastrophically damage or instantly destroy operational satellites. This endangers the vital services (like GPS, weather forecasting, and global communication) that modern society relies upon.

- Risk to Human Safety: The danger is amplified for crewed missions. Astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) face a constant, though statistically small, risk, with collision avoidance maneuvers sometimes required to ensure their survival and the integrity of the station.

The accumulating nature of this problem—a phenomenon known as the Kessler Syndrome—suggests that once the density of objects in low Earth orbit reaches a critical threshold, collisions will cascade, generating more debris and making some orbital paths virtually unusable. Addressing this unseen but accelerating orbital pollution is paramount for safeguarding the future of space exploration and utilization.

Defining Orbital Debris: The Cosmic Cleanup Challenge

What Exactly Is Space Debris?

Space debris, often interchangeably termed orbital debris or “space junk,” is the collective classification for any nonfunctional, human-made object currently orbiting the Earth. Far from being a natural phenomenon, this clutter represents the residual waste of more than six decades of space exploration and technological development.

Components of Space Junk

Orbital debris is not uniform; it encompasses a wide spectrum of materials and sizes. The most common components include:

- Defunct Satellites: These are spacecraft that have reached the end of their operational lives, have malfunctioned, or have exhausted their fuel supply, leaving them adrift in orbit.

- Spent Rocket Stages (Upper Stages): After a rocket successfully deploys its payload, the upper stages often remain in orbit. These large metallic cylinders are among the most massive pieces of debris.

- Collision and Explosion Fragments: This is perhaps the most concerning category. When two objects (like two satellites or a satellite and a rocket body) collide, or when an object explodes (often due to residual fuel), the result is a cloud of thousands of smaller, high-velocity pieces.

- Mission-Related Debris (MRD): This includes smaller objects, such as protective covers, lens caps, straps, pieces of insulation, and even tools lost by astronauts during spacewalks.

The Critical Danger of High Velocity

While the term “junk” might suggest something benign, the physics of orbit transform even the smallest item into a lethal projectile. The critical danger lies in the extreme speed at which these objects travel.

In Low Earth Orbit (LEO), debris orbits at speeds that can exceed $28,000 \text{ km/h}$ (roughly ten times the speed of a rifle bullet). Due to this immense kinetic energy (where $E_k = \frac{1}{2} m v^2$), a collision with even a minute piece of debris—for example, a flake of paint less than a centimeter across—can impart a substantial amount of damage. At this velocity, the impact can be catastrophic, capable of:

- Rendering Operational Satellites Nonfunctional: A high-speed impact can compromise sensitive instruments or breach the structure of vital communication and weather satellites.

- Threatening Crewed Spacecraft: It poses a significant, ongoing risk to the integrity of the International Space Station (ISS) and the safety of its astronaut crews.

The rapid fragmentation following a single collision can thus initiate a self-sustaining cycle, dramatically increasing the overall debris population, a scenario known as the Kessler Syndrome.

The Mechanics of Orbital Clutter: How Space Debris Accumulates

The establishment of humanity’s presence in space, beginning with the historic launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, initiated a slow but persistent process of populating Earth’s orbital pathways. Since that time, nearly every aerospace activity has the potential to contribute to the orbital debris problem.

Key Contributors to Accumulation

The accumulation of this “space junk” is not random; it stems from the inherent consequences of complex space missions:

- Routine Operations: Every time a rocket is launched, it leaves behind spent upper stages and potentially jettisoned fairings. Similarly, the deployment of new satellites can involve releasing protective shrouds and separation mechanisms.

- Mission Failures and Explosions: Malfunctions, accidental explosions (often caused by residual fuel igniting in spent rocket bodies), and minor operational mishaps can instantly shatter large objects, releasing thousands of fragments into orbit.

- Collisions: This is the most dangerous contributor to debris growth. When two massive objects collide, the impact generates a massive, high-velocity cloud of new debris.

The Exponential Risk

A landmark event vividly demonstrated this exponential danger: the 2009 collision between the operational Iridium 33 communications satellite and the defunct Russian Cosmos 2251 satellite. This single, catastrophic accident immediately produced thousands of detectable fragments, exponentially increasing the risk profile for every other object operating in that altitude band.

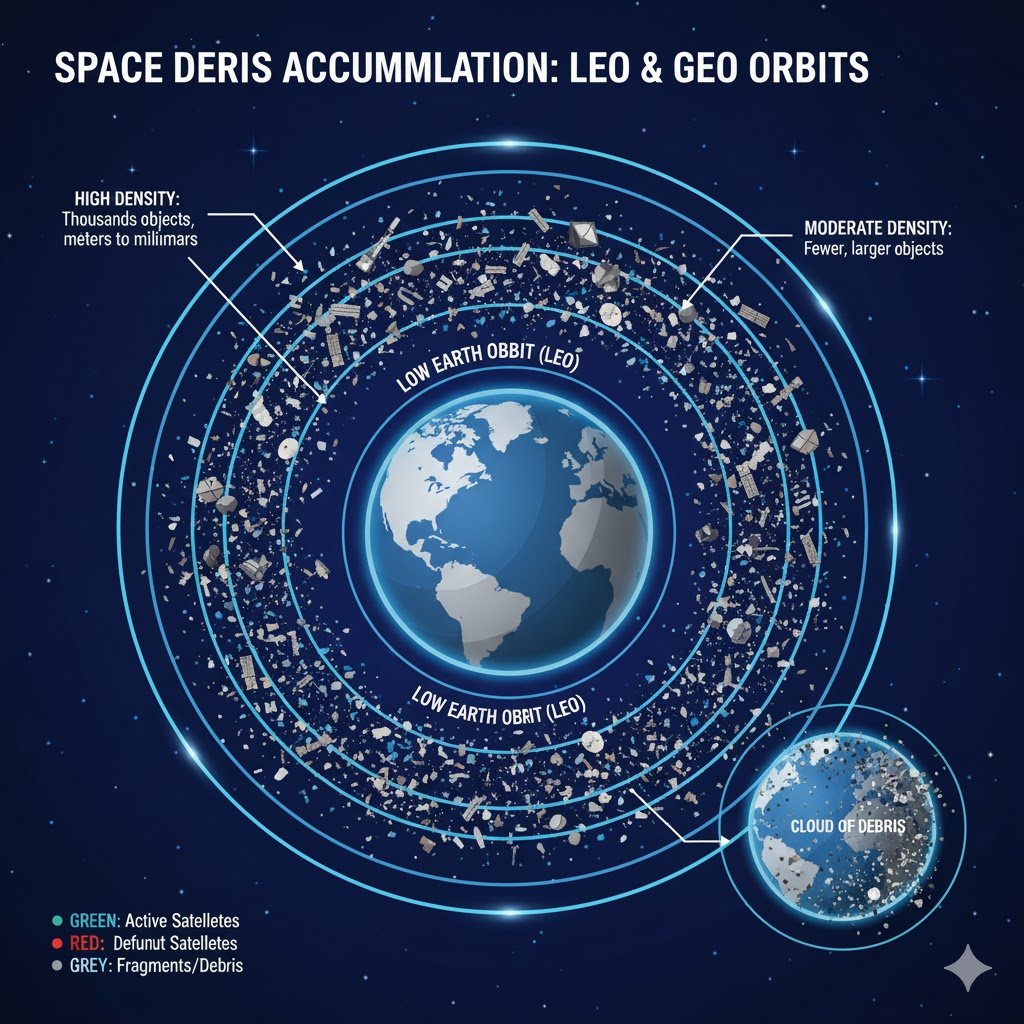

Forming the Debris Cloud

Over decades, these fragments, along with dead satellites and spent rockets, have coalesced to form a dense, hazardous cloud, particularly concentrated in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). LEO is the most utilized region of space, home to the majority of Earth observation, navigation, and telecommunication satellites, as well as the International Space Station (ISS).

The critical danger is that this accumulation is self-perpetuating. As the density of objects in LEO increases, the probability of future collisions rises proportionally. This feedback loop is the central tenet of the Kessler Syndrome: a hypothetical scenario where one collision triggers others in a chain reaction, eventually rendering specific orbital paths so cluttered that they become unusable for decades or even centuries.

The Critical Repercussions of Orbital Debris

The pervasive presence of orbital debris (or space junk) translates directly into immediate and long-term threats to both active space infrastructure and human personnel in orbit. These consequences jeopardize essential global services and significantly complicate the future of space exploration.

Direct Threat to Operational Satellites

The primary victims of orbital debris are the thousands of operational satellites that form the backbone of modern global infrastructure.

- Catastrophic Impairment: Even minute particles—flecks of paint or tiny metal fragments—become highly destructive projectiles due to their immense speed (potentially over $28,000 \text{ km/h}$). An impact at this velocity can easily puncture solar panels, shatter sensitive optical instruments, or critically damage antennas and communication hardware, often rendering an expensive satellite completely inoperable.

- Disruption of Services: The destruction or degradation of a single satellite has a ripple effect, disrupting vital terrestrial services. These include:

- Global Communication: Impacting everything from mobile networks to internet access.

- Navigation Systems: Affecting GPS and other crucial positioning services.

- Earth Observation: Undermining weather forecasting, climate monitoring, and disaster relief efforts.

Elevated Risk to Human Safety

Crewed space missions, particularly the International Space Station (ISS), face an ever-present, direct physical danger from space debris.

- Breach of Protection: While the ISS is equipped with protective layers (like Whipple shields designed to disperse the energy of small impacts), larger, untrackable pieces of debris pose a grave hazard. An impact can breach the station’s hull, causing rapid depressurization, equipment failure, and an immediate risk to the lives of the astronauts aboard.

- Avoidance Maneuvers: To mitigate this risk, flight controllers must constantly monitor potential close approaches. When a threat is identified, the ISS or other crewed vehicles must sometimes execute costly and time-consuming Debris Avoidance Maneuvers (DAMs), burning precious fuel and disrupting crew schedules.

Future Mission Complications

The growing density of the debris cloud imposes profound limitations on all prospective space activities.

- Increased Costs and Design Constraints: New spacecraft must be engineered with heavier, more robust, and more expensive protective shielding. This added mass requires more powerful rockets and increases overall launch costs, effectively taxing all future missions.

- Constrained Launch and Operation Windows: Mission planners must factor in the orbital positions of known debris fields. This narrows the available launch windows and constrains the permissible operational orbits for new satellites, limiting access to certain regions of space and complicating constellation management.

Global Strategies for Debris Mitigation and Management

The escalating threat posed by orbital debris has spurred a concerted, international effort among space agencies and private aerospace companies to develop a comprehensive set of solutions aimed at both reducing the existing junk and preventing future accumulation.

Proactive Tracking and Surveillance

Effective mitigation begins with knowing exactly what is in orbit. Organizations globally, such as the U.S. Space Command, meticulously track over $30,000$ pieces of debris larger than $10$ centimeters.

- Collision Avoidance: The resulting data is crucial for Space Situational Awareness (SSA). Satellite operators rely on these systems to receive timely collision warnings, allowing them to calculate and execute trajectory adjustments (Debris Avoidance Maneuvers, or DAMs) to safeguard their active spacecraft. This proactive monitoring is the first line of defense.

Developing Active Debris Removal (ADR) Technologies

The ultimate goal for existing debris is Active Debris Removal (ADR)—physically taking junk out of its operational orbit. While still in the developmental or demonstration phase, several innovative concepts are being explored:

- Capture Mechanisms: This includes specialized devices like robotic arms to securely grasp defunct satellites, large nets to ensnare smaller objects, or harpoons designed to pierce and secure targets for deorbiting.

- Energy-Based Removal: Researchers are exploring the use of powerful ground-based lasers to carefully nudge smaller debris into lower altitudes, increasing atmospheric drag and causing them to eventually burn up safely during re-entry.

Implementing Sustainable Design and Protocols

To ensure that today’s launches don’t become tomorrow’s debris, the focus is shifting towards orbital sustainability.

- “End-of-Life” Deorbiting: Modern satellite design increasingly incorporates mechanisms to ensure responsible removal. This is often achieved through mandatory end-of-life protocols that require satellites (especially those in Low Earth Orbit, LEO) to use residual fuel to propel themselves into the atmosphere for safe burn-up, or into a designated graveyard orbit within $25$ years of mission completion.

- Design for Demise (DfD): New spacecraft are being built with materials and designs that ensure they completely disintegrate upon atmospheric re-entry, minimizing the risk of large components surviving to impact Earth.

International Governance and Cooperation

The orbital environment is a shared global resource, necessitating collective action.

- Establishing Guidelines: Spacefaring nations are actively engaged in negotiations through bodies like the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) to establish and adhere to stringent guidelines and standards that minimize the creation of new debris.

- Policy Harmonization: These efforts aim to standardize mission planning and disposal practices globally, ensuring a safer, shared orbital environment for the benefit of all users.

The Path Forward: Safeguarding the Future of Space Access

As humanity continues its relentless drive to venture deeper into the cosmos—establishing permanent presences and launching ambitious exploratory missions—the challenge of managing orbital debris transitions from an abstract technical issue to an absolute necessity. The way we address this problem today will fundamentally define the viability of space utilization for generations to follow.

The Stakes of Inaction

Ignoring the pervasive threat of space junk carries severe, compounding risks:

- Orbital Lockdown: Allowing the accumulation to continue unchecked could activate the catastrophic Kessler Syndrome. This would render critical orbital pathways, particularly the economically vital Low Earth Orbit (LEO), so polluted that they would become practically unusable for decades, effectively cutting off our primary access point to space.

- Hindrance to Exploration: Every future mission—from deploying vital communications infrastructure to launching deep-space probes—would face significantly increased complexity, risk, and cost due to the requirement for heavy shielding and constant avoidance maneuvers. This directly hinders the pace and scope of future exploration.

- Endangerment of Human Life: The safety of astronauts aboard the International Space Station (ISS) and future orbital habitats will remain perpetually compromised, increasing the probability of a fatal collision.

The Essential Pillars of Sustainability

Moving forward, the collective responsibility of all spacefaring entities must be anchored in three crucial pillars:

- Proactive Debris Management: This involves establishing and strictly enforcing sustainable design principles for all new missions, including mandatory end-of-life deorbiting protocols that ensure objects do not remain in orbit beyond their operational lifespan.

- Technological Innovation: We must accelerate the development and deployment of Active Debris Removal (ADR) technologies—be it advanced robotic capture systems, efficient debris sweepers, or novel propulsion methods to nudge retired objects out of harm’s way.

- Robust Global Cooperation: Since debris respects no borders, the solution must be multilateral. Coordinated effort and binding international guidelines, negotiated through bodies like the UN, are essential to create a shared framework that governs orbital conduct and ensures a commitment to a safe and accessible orbital environment for all nations.

Ultimately, by embracing these responsibilities, we ensure that the final frontier remains a platform for discovery, not a junkyard of our own making.

FAQ – The Orbital Debris Challenge

Q1: What constitutes space debris?

A: Space debris, formally referred to as orbital debris or popularly as “space junk,” is the collection of all non-functional objects of human origin currently circling the Earth. This inventory ranges drastically in size, encompassing massive, defunct structures like retired satellites and spent rocket boosters, down to microscopic fragments resulting from previous collisions, explosions, or simple material degradation (such as paint flecks). Crucially, despite being non-functional, these pieces remain subject to orbital mechanics.

Q2: How does orbital debris accumulate and form?

A: The accumulation process began with the very first rocket launches in the late 1950s. Debris forms and grows through several mechanisms:

- Accidental and Deliberate Explosions: Malfunctions in old rocket stages (often due to residual fuel ignition) or deliberate tests (like the 2007 Chinese anti-satellite missile test) shatter large objects into thousands of pieces.

- Collisions: High-velocity impacts between two orbital objects (e.g., the 2009 Iridium-Cosmos event) are the most significant generators, creating vast, high-speed clouds of fragments.

- Mission-Related Litter: Components routinely jettisoned during satellite deployment or lost tools during spacewalks contribute to the clutter.

Q3: Why is space debris considered a critical danger?

A: Orbital debris is dangerous primarily due to extreme velocity. In Low Earth Orbit (LEO), objects can travel at speeds exceeding $28,000 \text{ km/h}$. At this speed, even tiny particles possess immense kinetic energy. This poses a dual threat:

- Infrastructure Damage: Even a small, untraceable piece can catastrophically damage or instantly destroy operational satellites, disrupting global communication, weather forecasting, and navigation services.

- Astronaut Safety: The debris poses a direct, life-threatening risk to the ISS and other crewed missions, as an impact could breach protective shielding or the station’s hull.

Q4: What is the significance of the Kessler Syndrome?

A: The Kessler Syndrome is a theoretical, worst-case scenario proposed by NASA scientist Donald Kessler. It describes a tipping point where the density of debris in a specific orbit reaches a critical threshold. At this stage, one collision is highly likely to trigger a chain reaction of subsequent collisions, creating exponentially more debris. If this cascade were to occur, it could make certain vital orbits virtually unusable for centuries due to the sheer volume of destructive, high-speed projectiles.

Q5: How do space agencies monitor and track space debris?

A: Global organizations, notably the U.S. Space Command and the European Space Agency (ESA), utilize a vast network of ground-based radars and telescopes to maintain a catalog of over $30,000$ detectable pieces of debris (generally larger than $10 \text{ cm}$). This information forms the basis of Space Situational Awareness (SSA). Satellite operators rely on these tracking systems to receive precise collision warning alerts, allowing them to initiate Debris Avoidance Maneuvers (DAMs) to ensure the safety of their active spacecraft.

Q6: What technological solutions are being developed to manage and remove debris?

A: Solutions fall into two categories:

- Active Debris Removal (ADR): This involves innovative concepts designed to physically capture and deorbit existing junk. Technologies under development include sophisticated robotic grasping arms, specialized capture nets and harpoons, and even precise ground-based lasers to gently nudge fragments into the atmosphere for safe burn-up.

- Mitigation: This focuses on preventing future debris. It mandates the use of sustainable design principles, such as incorporating “end-of-life” protocols that ensure satellites automatically deorbit (or move to a graveyard orbit) within a designated timeframe, typically $25$ years after mission completion.

Q7: How does the presence of debris impact the future of space exploration?

A: The growing orbital population significantly complicates future endeavors. It directly increases collision risks for new satellites, forcing mission planners to implement costly and heavy protective shielding. This added mass increases launch expenses and limits the payload capacity. Furthermore, the necessity of avoiding known debris fields places restrictions on launch windows and the choice of operational orbits, potentially hindering large-scale projects like satellite mega-constellations.

Q8: What role can ordinary people play in addressing the space debris problem?

A: While individuals don’t launch rockets, public awareness and advocacy are vital. People can contribute by:

- Supporting Research and Policy: Backing government policies and international guidelines that mandate responsible orbital practices and fund debris removal research.

- Promoting Sustainability: Encouraging private companies to adopt best practices for satellite disposal and life-cycle management.

- Raising Awareness: Educating others about the risk of the Kessler Syndrome and the importance of preserving the orbital environment for future generations.