Table of Contents

Rogue Planets: The Lone Drifters of the Cosmos

In the vast, star-dusted expanse of the Milky Way galaxy, a mysterious class of celestial bodies exists, challenging our traditional understanding of planetary systems. These are rogue planets (also known as free-floating planets or interstellar planets), worlds that wander in absolute isolation, far removed from the comforting, life-giving warmth of a parent star. They are the quintessential solitary travelers of the cosmos, untethered to any star system and forever traversing the profound darkness of interstellar space.

Origins and Isolation

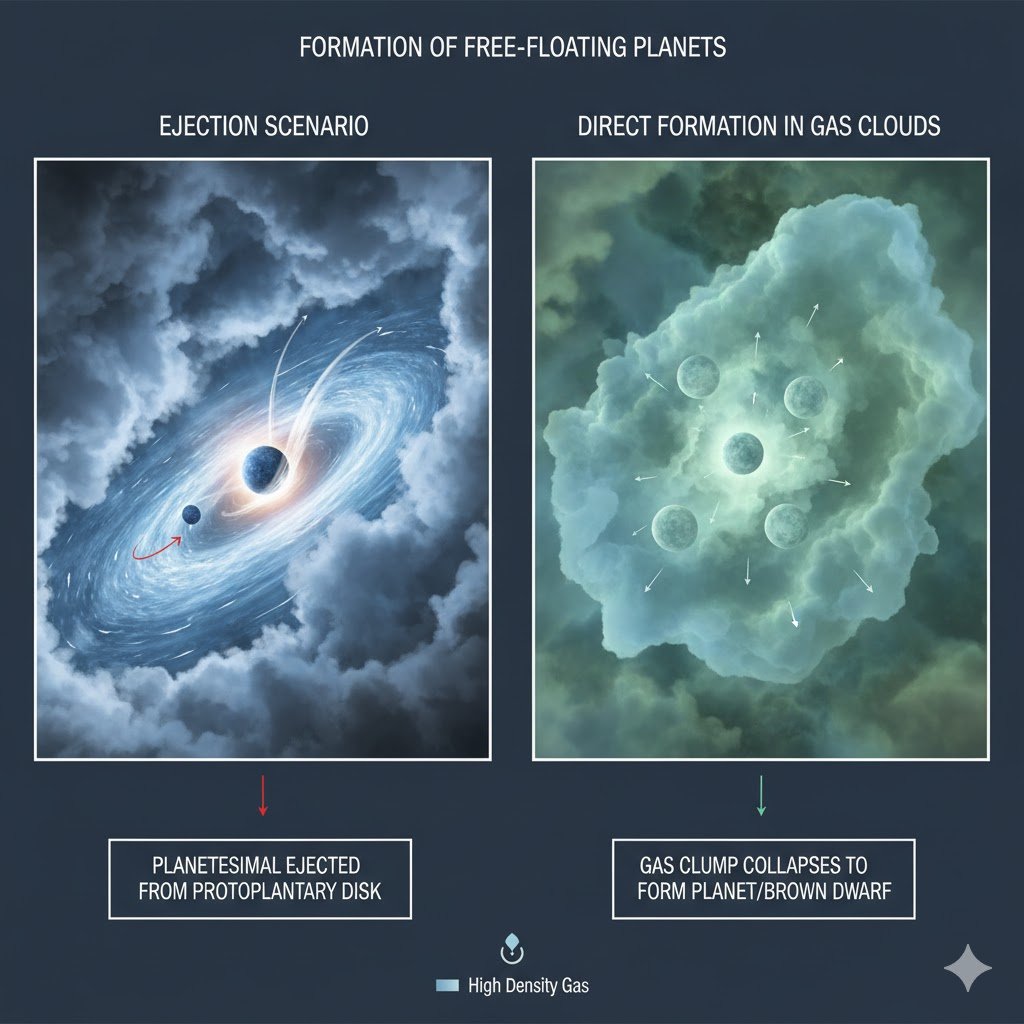

Unlike the familiar planets of our solar system, which dutifully revolve around the Sun within its gravitational well, rogue planets follow independent, elliptical trajectories around the galactic center. Their origins are primarily attributed to two powerful and often violent processes:

- Planetary Ejection: The most common theory suggests that rogue planets form initially within a young, dynamic star system, just like any other planet. However, during the chaotic early phases of formation, or through subsequent close gravitational encounters with massive stellar bodies (like a giant planet or a passing star), the smaller planet is gravitationally slingshotted or “kicked out” of its home orbit. This immense force overcomes the star’s gravitational pull, sending the planet hurtling into interstellar space.

- Formation in Isolation: Less commonly, some theories posit that a few rogue planets might form directly from small pockets of gas and dust that collapse on their own, far from any star. However, these objects would need to be large enough to be classified as a planet (usually below the brown dwarf mass limit, which is about $13$ times the mass of Jupiter, $M_J$).

The Challenge of Detection

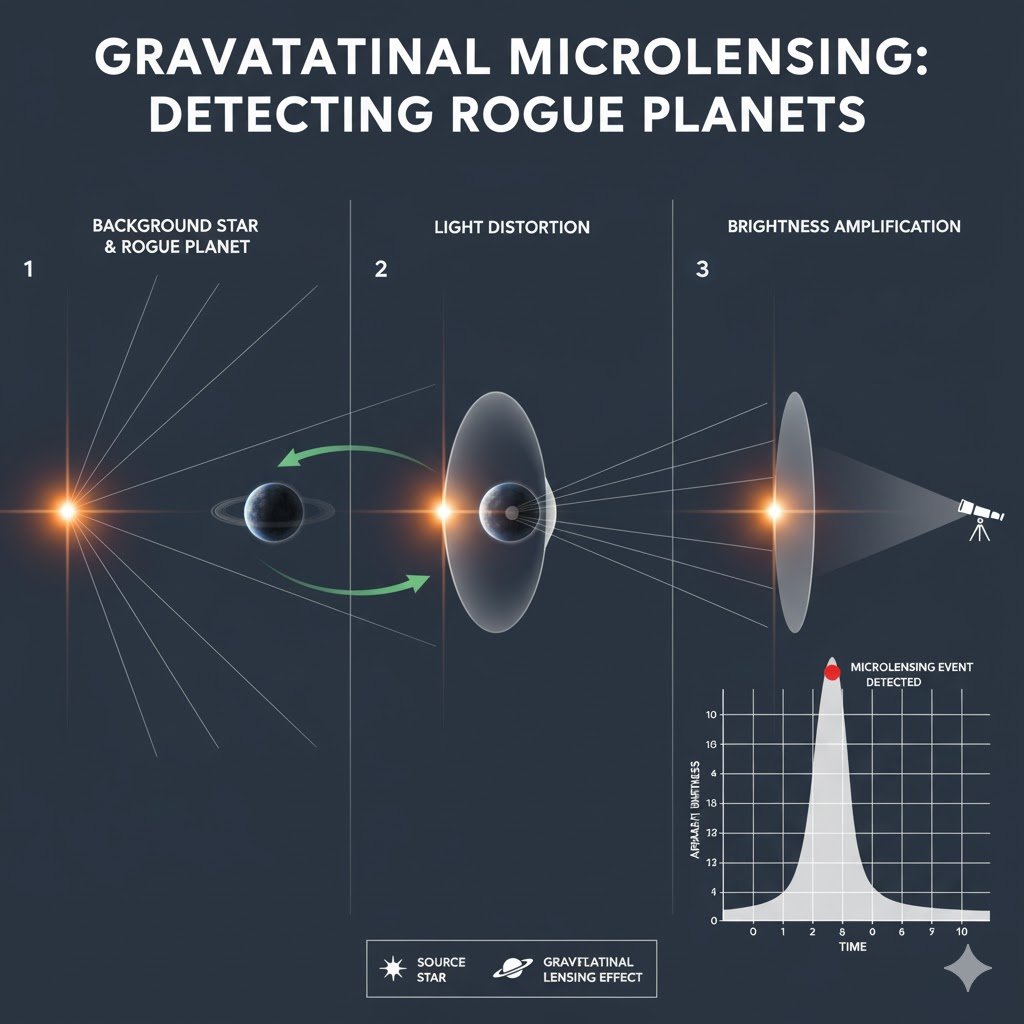

One of the most profound aspects of rogue planets is their inherent invisibility. They do not emit their own light, and without a nearby star to illuminate them, they are essentially invisible to conventional telescopes. Detecting these cold, dark worlds relies on sophisticated and rare astronomical events, primarily using the technique of gravitational microlensing.

- Gravitational Microlensing: According to Einstein’s theory of General Relativity, a massive object (the rogue planet) passing between Earth and a distant background star will momentarily magnify and brighten the star’s light. This effect occurs because the planet’s gravity warps spacetime, acting like a temporary lens. The duration and shape of this brightening event allow astronomers to infer the mass of the unseen object. Due to the fleeting and unpredictable nature of this alignment, dedicated monitoring campaigns, such as the OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment), are crucial for their discovery.

Scientific Significance

The study of these lonely travelers offers astronomers profound insights across several key areas of planetary science and galactic evolution:

- Planet Formation Mechanisms: The sheer number of rogue planets—potentially outnumbering the stars in the Milky Way by a significant margin—indicates that planetary ejections are a common and highly efficient mechanism in the galaxy. Studying them helps refine our models of how stellar systems are born and evolve under the influence of strong gravitational dynamics.

- Galactic Mass Inventory: Rogue planets represent a substantial portion of the galaxy’s baryonic (normal) matter that was previously unaccounted for. Determining their total population is vital for a complete inventory of the Milky Way’s mass distribution.

- Exotic Environments and Astrobiology: Perhaps the most speculative, but intriguing, insight relates to astrobiology. If a rogue planet is massive enough, it could retain a thick atmosphere capable of insulating its surface. Furthermore, geothermal activity powered by radioactive decay in the core could sustain liquid water beneath a massive, icy crust, potentially creating subsurface oceans where primitive life could survive, shielded from the harsh radiation of interstellar space. These would be truly exotic, self-contained biospheres.

Studying rogue planets transforms our view of the universe, showing us that the majority of worlds may not orbit a star, but instead traverse the cosmic dark as independent, fascinating entities.

The Untethered Worlds: Defining Rogue Planets

Rogue planets, officially known as free-floating planets (FFPs) or interstellar planets, represent a distinct and enigmatic class of celestial bodies. They are defined as planetary-mass objects that exist without a gravitational bond to any star, traversing the deep darkness of interstellar space alone. They are far more than just distant exoplanets; they are true, untethered wanderers of the cosmos, making their way independently across the vast expanse of the galaxy.

Size, Abundance, and Composition

The sheer potential number of these nomadic worlds is staggering, radically transforming our view of the galactic population.

- Abundance: Current estimates, based on microlensing surveys, suggest that the Milky Way could host billions of these rogue worlds, potentially outnumbering the stars themselves by a factor of one hundred or more. This makes them a dominant component of the galaxy’s overall mass budget that was largely unaccounted for until recently.

- Mass Range: These objects span the entire planetary size spectrum. They can be small, rocky worlds comparable to Earth or Mars, or colossal gas giants exceeding the mass of Jupiter. The defining physical constraint for a rogue planet is that its mass must be below the thermonuclear fusion threshold—less than approximately $13$ times the mass of Jupiter ($13 M_J$). Objects above this limit are classified as brown dwarfs, which are considered failed stars.

- Potential for Systems: Despite their isolation from a star, rogue planets aren’t necessarily simple, singular bodies. Much like planets in a star system, they can theoretically retain or capture smaller objects, meaning some may host their own entourage of moons or even complex ring systems.

The Mechanism of Ejection

The current scientific consensus points to dynamical ejection as the primary source of these planetary nomads.

- Violent Origins: Most rogue planets are thought to have formed conventionally within the dynamic environment of a young, chaotic star system. In these dense, competitive nurseries, powerful gravitational interactions occur frequently.

- Gravitational Slingshot: When a smaller planet has a close encounter with a much more massive object—like a forming gas giant or a passing binary star—it can be subjected to an immense gravitational force. This force acts as a slingshot, accelerating the planet to a velocity high enough to overcome the star’s gravitational pull entirely, flinging it out of its home system and into the interstellar void.

Environment and Habitability

The environments on these cold worlds are radically different from anything in our solar system, yet they harbor a fascinating, albeit remote, potential for sustaining life.

- The Deep Freeze: Without a stellar heat source, the surface temperatures on rogue planets are likely to hover near absolute zero, creating a frozen, dark landscape.

- Internal Heat for Life: The key to their potential habitability lies in internal processes. If a rogue planet is sufficiently massive, it can retain a thick, insulating atmosphere. More crucially, geothermal heat generated by the decay of radioactive elements within the planet’s core could be intense enough to sustain subsurface liquid water oceans beneath a massive, icy crust. This internal energy could provide the necessary warmth for chemosynthetic life, creating a truly unique and self-contained biosphere.

How Do Rogue Planets Form?

Rogue planets, the solitary travelers of the galaxy, primarily come into existence through two distinct cosmic processes: the violent eviction from a home system or independent birth from primordial gas and dust.

Ejection from Planetary Systems (The “Kick-Out” Scenario)

The dominant theory suggests that most rogue planets begin their lives as conventional planets within the turbulent embrace of a star system. Their journey into isolation is a consequence of chaotic and powerful gravitational dynamics.

- The Early Chaos of Planet Formation: Young star systems are incredibly dynamic and unstable. They are often characterized by dense nebulae, numerous planetesimals, and newly formed planets that haven’t settled into stable orbits. This density creates fertile ground for disruptive gravitational encounters.

- The Gravitational Slingshot: The critical event is a close three-body interaction. When a smaller planet comes into proximity with a much more massive body—typically a giant planet like Jupiter or Saturn, or perhaps a passing companion star in a binary or multiple-star system—the resulting gravitational pull acts like a powerful slingshot. The massive object transfers immense kinetic energy to the smaller planet.

- Overcoming Stellar Gravity: If the energy transfer is significant enough, the smaller planet’s velocity exceeds the escape velocity of the star system. It is then violently ejected from its orbit, cast out into the icy blackness of interstellar space.

- Bearing a History: Rogue planets created this way carry the geological and chemical signature of their birth system. Analyzing their composition can provide crucial insights into the environment where they formed, including the location of the snow line and the processes of planetary migration that occurred before their eviction.

Direct Formation from Gas Clouds (The “Born Alone” Scenario)

A smaller, yet fascinating, subset of rogue planets may never have experienced the light of a star. These worlds form in isolation, a process that truly blurs the traditional lines between planets and stars.

- Mini-Collapses: In the vast molecular clouds where stars are born, there are occasionally small pockets of gas and dust that reach a critical density. These isolated clumps begin to collapse under their own self-gravity, just like the material that forms a star.

- Failing to Ignite: The resulting object grows into a planetary-mass body but never accumulates sufficient mass to trigger sustained thermonuclear fusion in its core. For this object to be classified as a rogue planet, its mass must fall below the $13 M_J$ threshold, which distinguishes it from a brown dwarf (a “failed star”).

- The Continuum of Objects: These objects represent the lowest-mass extension of the stellar formation process. Unlike ejected planets, which share a formation history with orbiting worlds, these directly-formed rogues have spent their entire existence free-floating. Studying them helps astronomers understand the minimum mass required for self-initiated collapse and provides a crucial link in the continuum of objects stretching from planets to the least massive stars.

The combination of these two processes—violent eviction and solitary formation—accounts for the estimated billions of rogue planets populating our galaxy.

Detecting the Invisible: The Science of Finding Rogue Worlds

The nature of rogue planets—their lack of visible light emission and their isolation from a nearby star—makes them inherently challenging to detect. They are essentially dark, cold masses drifting through the void. To confirm the existence of these elusive objects, astronomers must rely on highly sophisticated indirect detection methods that measure their faint influence on background light or nearby stars.

Gravitational Microlensing: The Primary Tool

The most successful and prolific method for discovering rogue planets relies on Einstein’s theory of General Relativity.

- The Principle: Gravitational microlensing occurs when a compact, foreground object (the rogue planet, or the “lens”) perfectly aligns with a much more distant background star (the “source”) as seen from Earth. The planet’s powerful gravity warps the fabric of spacetime, causing the light rays from the background star to bend and converge, acting like a giant, temporary lens.

- The Signature: This lensing effect results in a sharp, temporary brightening of the background star’s light, which can last from mere hours to a few days. The shape, duration, and intensity of this magnification event allow astronomers to calculate the mass of the unseen object.

- Survey Efforts: Dedicated astronomical campaigns, such as the OGLE (Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) and KMTNet (Korean Microlensing Telescope Network), constantly monitor millions of stars in the crowded galactic bulge to catch these fleeting events. Microlensing has been responsible for confirming the existence of several dozen rogue planets, ranging from Mars-sized to Jupiter-sized objects.

Infrared Observation: Catching the Faint Glow

While older rogue planets are utterly cold, young rogue planets offer a brief window of opportunity for direct observation.

- Residual Heat: When a planet forms, the energy from gravitational contraction and accretion generates significant heat. A newly formed rogue planet retains this residual thermal energy, causing it to emit a faint, persistent glow in the infrared (IR) spectrum.

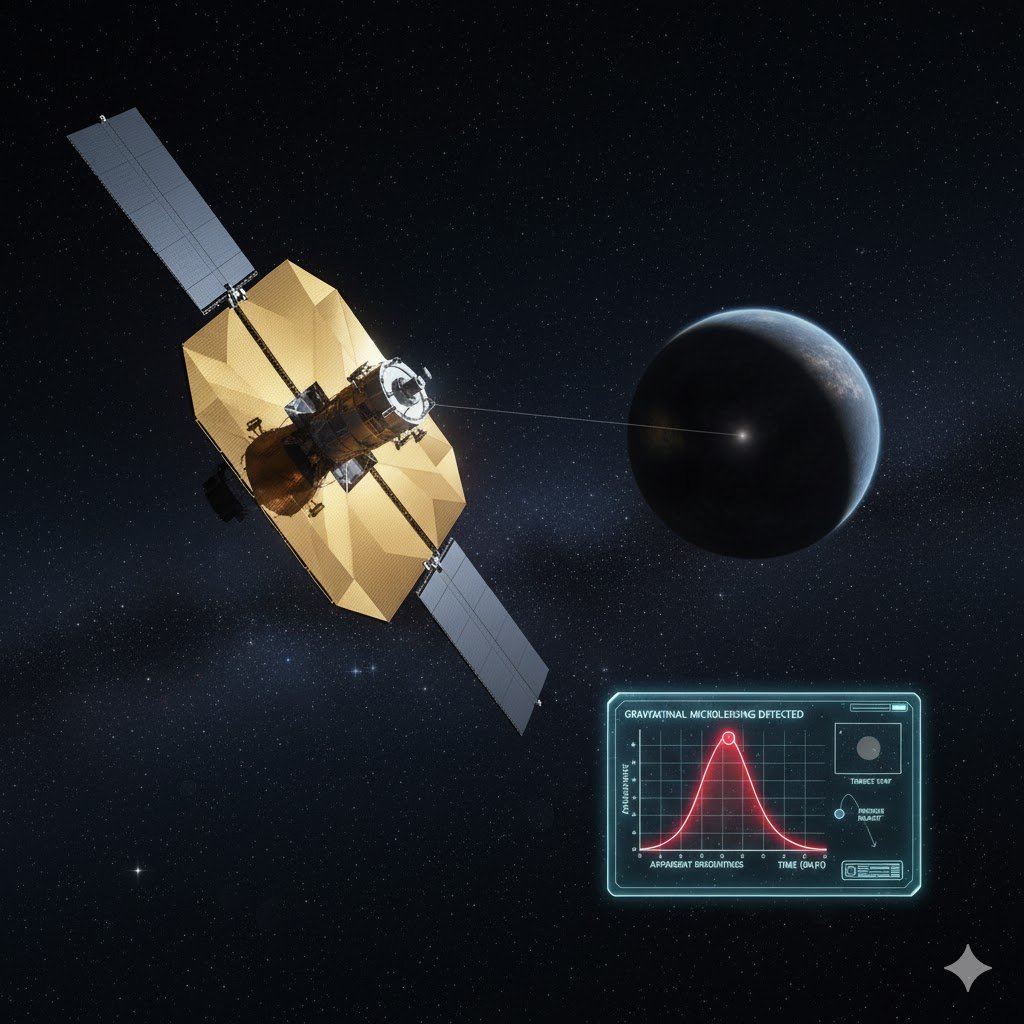

- Telescope Sensitivity: Detecting this faint heat requires incredibly sensitive instruments, like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) or large ground-based telescopes equipped with adaptive optics. JWST’s powerful infrared capabilities are particularly suited for this task, allowing it to image these warm objects directly against the cool background of space, especially those less than a few hundred million years old.

Astrometry and Radio Waves: Measuring the Tug

These techniques rely on precisely measuring the effect of the rogue planet’s gravity on neighboring bodies.

- Astrometry: This involves the precise measurement of the positions and movements of stars. Even an unseen rogue planet orbiting extremely far from a star, or just passing nearby, will exert a subtle gravitational tug. Over years of observation, this pull manifests as a slight, periodic or non-periodic wobble or displacement in the star’s apparent position on the sky.

- Radio Detection: Although speculative, some theorize that the complex interaction of a rogue planet’s magnetic field with the interstellar medium could generate low-frequency radio waves. Future, highly sensitive radio telescopes might be able to pick up this unique, non-thermal signature.

Despite these advanced technical efforts and the estimated billions of rogues, the confirmed count remains relatively small—only a few dozen have been fully verified. This underscores how truly mysterious and elusive these interstellar drifters remain, representing a frontier in modern astrophysics.

The Profound Significance of Rogue Planets

Studying rogue planets is far more than a curious academic pursuit; it is a vital mission that offers unique and transformative insights into planetary science, galactic dynamics, and the potential for life beyond Earth. These isolated worlds hold key pieces of the cosmic puzzle that orbiting planets simply cannot provide.

Clues to Planetary Formation and System Stability

The existence and estimated sheer number of rogue planets offer critical constraints on our models of how planets form and evolve.

- Evidence of Ejection Efficiency: The high frequency of rogue planets—potentially outnumbering stars—strongly indicates that dynamical instability and ejection are highly common and efficient processes across the galaxy. This data forces astronomers to refine theories of core accretion and disk instability, particularly in multi-planet systems where massive gravitational interactions are inevitable.

- Galactic Mass Inventory: Rogues represent a significant, previously unaccounted-for population of baryonic (normal) matter. Accurately tallying their numbers is essential for a complete inventory of the Milky Way’s total mass, influencing our understanding of the galaxy’s rotation and overall structure.

- Shedding Light on Stability: The prevalence of these ejected worlds is a direct measure of the instability of young planetary systems. It helps astronomers calculate the probability of a system maintaining its planets in stable orbits, thereby highlighting which architectural configurations (e.g., specific planet mass ratios and spacing) are most likely to survive the tumultuous early years.

Understanding Star and Planet Interactions (Cosmic Fossils)

Rogue planets are invaluable as “fossils” of the violent, early history of star systems.

- Fingerprints of Migration: The ejection event itself is often the final act following phases of planetary migration, where giants move inward or outward, stirring up the smaller bodies. Rogue planets carry the chemical and isotopic fingerprints of their birth location within the star-forming disk, allowing scientists to trace the history of these colossal reshuffling events that occurred billions of years ago.

- The Final Architecture: Rogue planets offer a window into the chaotic close encounters between stars and planets that ultimately shape the final, stable architecture of surviving systems like our own Solar System. By studying the velocity and composition of these travelers, scientists can reverse-engineer the energy and mass of the object that delivered the final, system-shattering “kick.”

Exotic Potential Environments and Habitability

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of rogue planets is the possibility of exotic habitability, challenging our Earth-centric view of life.

- The Subsurface Ocean Hypothesis: While the surface of a rogue planet, far from stellar warmth, is likely a deep-frozen wasteland, a substantial internal heat source could change everything. Radioactive decay within the planet’s core (primarily of isotopes like uranium, thorium, and potassium-40) can generate enough thermal energy to sustain a layer of liquid water beneath a kilometers-thick icy crust.

- Self-Contained Biospheres: If these subsurface oceans exist, they could represent self-contained biospheres entirely independent of stellar energy. Any life within would be chemosynthetic, thriving on chemical reactions generated by hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, much like some life forms deep within Earth’s oceans.

- Challenging Habitability Models: These hypothetical environments dramatically expand the concept of the Habitable Zone, suggesting that life could be possible not only within the narrow orbital band around a star but also throughout the vast, dark emptiness of the galaxy.

The study of these isolated worlds forces us to look beyond the star and consider the planet itself as a potential energy source for life.

Rogue Planets in Popular Culture: A Canvas for Mystery

The inherent drama and existential mystery of rogue planets—worlds adrift in perpetual darkness—have naturally captured the collective imagination, making them a recurring and compelling feature across science fiction literature, film, and video games. They serve as potent narrative devices that explore themes of isolation, survival, and the unknown depths of the cosmos.

Themes and Narrative Devices

In storytelling, rogue planets are often used to immediately establish a tone of danger and profound alienation:

- Ultimate Isolation: Their starless nature symbolizes the utter limit of isolation. A starless sky means no fixed seasons, no dependable light, and no easy navigation, creating a hostile environment that tests the resilience of any characters who encounter it.

- The Treacherous Obstacle: In interstellar travel narratives, rogue planets frequently appear as invisible, high-speed hazards. Because they lack the easy visual markers of a nearby star system, they pose a genuine and terrifying threat of collision, forcing space navigators to rely on specialized, short-range detection systems.

- A Blank Slate for Life: The scientific theory that internal heat could sustain life beneath an icy crust makes them perfect settings for exotic biology. Writers often imagine strange, bioluminescent, or pressure-adapted life forms thriving in these dark, self-contained biospheres, creatures entirely unlike anything found on solar-powered worlds.

Notable Examples in Media

Rogue planets and similar starless bodies have been featured in a variety of high-profile franchises:

- The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU): The planet Sakaar, featured prominently in Thor: Ragnarok, serves as a prime cinematic example. While not strictly a planet with no star, it is a world existing on the far edge of a wormhole network, largely composed of space debris and existing under a peculiar, artificial-looking red glow (suggestive of a starless or dying system). Its existence as a dumping ground for the galaxy’s castoffs perfectly mirrors the concept of an isolated world far from organized systems.

- The Wandering Earth (Liu Cixin): Perhaps the most direct and dramatic use of the concept, this acclaimed Chinese novel (and subsequent film adaptation) features a monumental scenario where Earth itself is deliberately converted into a rogue planet. Equipped with gigantic thrusters, the planet is driven out of the Solar System to escape the Sun’s impending death, highlighting the terrifying vulnerability of a planet without a star and the immense struggle required for collective human survival.

- Classic Sci-Fi Literature: In foundational science fiction, rogue planets often feature as settings for short stories exploring extreme survival. For example, some authors depict vast, frozen surfaces punctuated only by volcanic heat vents, where colonists must live entirely underground, relying on geothermal power—a direct nod to the potential geothermal habitability debated by astronomers.

In every portrayal, the rogue planet retains its core identity: a dark, mysterious world that forces characters—and audiences—to confront the terrifying fragility of life when stripped of the Sun’s dependable light.

Challenges in Studying Rogue Planets: Chasing Shadows

Despite their profound importance to planetary science, rogue planets are among the most enigmatic objects in astronomy. Their very nature—isolated and dark—presents immense technical and logistical hurdles that push the limits of modern observational technology.

Distance and Faintness: The Visibility Barrier

The most fundamental challenge is the inherent invisibility of these worlds.

- No Stellar Illumination: Lacking a parent star, rogue planets do not reflect light and only emit a faint glow from residual heat. This means they are almost impossible to observe directly in the visible spectrum.

- Extreme Distances: Many rogue planets are hypothesized to be scattered deep within the galactic halo and disk, often tens of thousands of light-years away from Earth. Detecting a cold, dark, Jupiter-sized mass at such extreme distances requires instruments with unparalleled sensitivity. Only with next-generation observatories, like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), can astronomers hope to capture the faint infrared radiation emitted by the youngest, warmest rogues.

Short Observational Windows: The Fleeting Alignment

The primary successful method for detection, gravitational microlensing, is inherently dependent on a brief, rare geometric alignment.

- Rarity and Rapidity: A microlensing event occurs only when the rogue planet perfectly passes between Earth and a background star. This alignment is fleeting, typically lasting anywhere from a few hours to a couple of weeks. The short duration makes it nearly impossible to confirm and characterize the planet before the event ends.

- Global Coordination: Discovering and following up on these events demands rapid response and international collaboration. Dedicated survey telescopes must scan the sky continuously, and upon detection, they must immediately alert larger, more powerful telescopes around the globe to gather follow-up data before the magnification fades.

Distinguishing from Brown Dwarfs: The Classification Quandary

The boundary between a massive rogue planet and a small brown dwarf (a “failed star”) is fuzzy, leading to classification difficulties.

- Mass Threshold: The strict scientific dividing line is the mass required to initiate deuterium fusion, which is approximately $13$ times the mass of Jupiter ($13 M_J$). Objects below this mass are planets; objects above are brown dwarfs.

- Difficulty in Measurement: However, measuring the exact mass of an object solely based on a microlensing curve is complex and prone to uncertainty. A large rogue planet (say, $10 M_J$) can look nearly identical to a low-mass brown dwarf (say, $15 M_J$) in terms of its lensing signature or even its thermal output, especially at vast distances. Accurately determining the mass often requires subsequent observations or complex modeling to ensure proper classification.

Overcoming these challenges necessitates a multi-pronged approach: the deployment of next-generation space-based telescopes for deep-field observation, the continuous refinement of microlensing detection algorithms, and a global, coordinated effort to efficiently track and confirm these elusive celestial bodies.

What Rogue Planets Reveal About the Galaxy

Rogue planets are far more than mere isolated oddities; they are crucial cosmic clues that help astronomers decode the evolutionary history, gravitational dynamics, and potential for life across the vast expanse of the Milky Way. Their very existence forces a fundamental reassessment of what constitutes a “typical” world.

Rewriting the Rules of Galactic Evolution

The sheer abundance of these interstellar travelers provides vital data that refines our models of how the galaxy operates on a massive scale.

- Ubiquity of Instability: Their large numbers—potentially outnumbering stars—strongly suggest that planet ejection is not a rare event but a highly common occurrence in star-forming regions. This implies that most newly formed planetary systems are dynamically unstable during their chaotic early stages, leading to gravitational “brawls” where planets are frequently thrown out. This realization fundamentally changes our understanding of the typical lifespan and stability of planetary architectures throughout the galaxy.

- Refining Galactic Models: Rogue planets significantly influence the overall mass budget of the Milky Way. Accounting for their mass, which was previously unseen, helps astronomers build more accurate models of the galaxy’s mass distribution, informing everything from the calculated star formation rates to the frequency of planetary systems. Their presence influences the gravitational dynamics of the galactic disk and bulge, providing a clearer picture of the non-luminous (non-star and non-dark matter) material populating the galaxy.

- The Fate of Planet Formation: Rogue planets, which carry the chemical and orbital signatures of their birthplace, serve as fossil evidence that helps establish how often planets are scattered and how systems achieve their final, stable configurations. They essentially document the historical failure rate of planetary stability.

Expanding the Boundaries of Habitability

The potential for life on rogue planets radically alters the concept of what a habitable world truly means.

- Beyond the Goldilocks Zone: Life, as we know it, is conventionally tied to a star’s Habitable Zone (or Goldilocks Zone)—the region where temperatures allow for liquid water on a planetary surface. Rogue planets shatter this restriction. Life on these dark worlds, if it exists, would thrive without sunlight, relying instead on internal energy.

- The Power of Internal Heat: The primary energy source for a rogue planet’s biosphere would be geothermal heat generated by the radioactive decay of elements deep within its core. This warmth could create and sustain vast, subsurface oceans of liquid water beneath a thick, insulating ice shell. This scenario, once relegated purely to science fiction, is now a serious focus for astrobiologists.

- A New Kind of Ecosystem: Such hypothetical ecosystems would be chemosynthetic, driven by chemical energy from hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, mirroring deep-sea life on Earth. This expands the notion of habitability from surface environments to planetary interiors, suggesting that the galaxy might be teeming with life on cold, dark worlds previously considered barren.

Studying rogue planets thus offers a dual reward: a clearer picture of the galaxy’s turbulent past and a much broader vision for the future of astrobiology.

The Future of Rogue Planet Exploration

The next decade promises a true revolution in our ability to detect and characterize rogue planets. Advances in both space-based and ground-based observatories are poised to dramatically expand our galactic census and shed light on these mysterious worlds, transitioning them from theoretical oddities to established astronomical targets.

Space-Based Infrared Pioneers

Space telescopes are crucial because they avoid the atmospheric distortion that blurs and absorbs the faint light from deep space.

- James Webb Space Telescope (JWST): JWST is the current frontrunner for direct observation. Its immense mirror and unprecedented sensitivity in the infrared spectrum are perfectly suited to the task. JWST’s primary role will be to confirm and characterize the youngest rogue planets—those that still retain significant residual heat from their formation. By analyzing the faint thermal emission, scientists can gain the first direct data on their atmospheric composition and temperature profiles, moving beyond simple detection to actual physical study. It is expected to provide some of the first high-resolution images of these isolated young worlds.

- Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (Roman): Planned for launch in the mid-2020s, Roman is set to become the ultimate surveyor of rogue planets. Equipped with a wide-field instrument, it will conduct dedicated, large-scale microlensing surveys targeting the dense star fields of the galactic bulge. Roman is projected to discover thousands of free-floating planets, including smaller, Earth-mass rogues, which are often too faint and brief for current ground-based facilities to reliably catch. Its findings will provide the most statistically robust estimate yet of the total rogue planet population in the Milky Way.

Ground-Based Observatories: Precision and Scale

Advanced ground-based facilities, utilizing cutting-edge adaptive optics and specialized instruments, will complement the work of space telescopes.

- Next-Generation Infrared Detectors: Massive ground-based telescopes, such as the upcoming Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), will be equipped with more powerful adaptive optics systems and highly sensitive infrared detectors. These improvements will allow astronomers to search for slightly older, colder rogue planets closer to our own Solar System. Because the gravitational microlensing effect is stronger for closer objects, these facilities will enhance the precision of mass and distance measurements for nearby rogues.

- Astrometric Follow-up: Future large telescopes will also be used for detailed astrometric follow-up. By continuously monitoring the positions of stars, they can detect the minute, long-term gravitational “wobble” caused by a nearby, unseen rogue planet, providing a detection method independent of the microlensing effect.

Transforming Our Understanding

This surge in observational capability will lead to profound discoveries:

- Refining Planetary Census: The thousands of discoveries expected from Roman will transform the rogue planet population estimate from a theoretical calculation into a confirmed, statistically solid count, officially adding a major new component to the galaxy’s planetary census.

- Astrobiology Reassessment: By characterizing the atmospheres of these worlds, scientists can test theories about the insulating properties of thick hydrogen-helium atmospheres. This empirical data will be critical for verifying the subsurface ocean hypothesis and fundamentally transforming our understanding of life’s potential, proving whether a starless existence can truly support habitable conditions.

Conclusion: The Silent Messengers of the Cosmos

Rogue planets stand as some of the most profound and intriguing inhabitants of the Milky Way galaxy. As lonely, untethered wanderers, they fundamentally challenge the long-held traditional view that a planet is defined solely by its orbit around a star. They prove that planetary mass objects can not only survive but may, in fact, dominate the galactic census by sheer numbers.

Unveiling Galactic Secrets

The study of these interstellar drifters is not merely an academic footnote; it’s a critical pursuit that unveils hidden stories about the galaxy’s turbulent history:

- Planetary Formation Dynamics: Their estimated abundance confirms that planetary ejection is a common, even prevalent, mechanism, revealing the violent and unstable nature of planetary systems during their formative stages. Rogue planets are essentially gravitational fossils, carrying the scars and chemical signatures of the chaotic systems that expelled them.

- Galactic Evolution and Mass: By quantifying the rogue planet population, astronomers can refine models of galactic evolution, gaining a more accurate inventory of the baryonic mass distributed throughout the Milky Way. These dark bodies significantly influence our understanding of the galaxy’s overall gravitational dynamics.

The Redefinition of Life’s Possibilities

Perhaps the most exciting implication of rogue planet research lies in the field of astrobiology. These cold worlds dramatically push the limits of habitability:

- Life Without Sunlight: They present the theoretical possibility of subsurface oceans warmed not by a star, but by the persistent power of internal radioactive decay. This scenario transforms the concept of the Habitable Zone from a narrow band of orbit around a star to a property inherent to the planet itself, suggesting that vast numbers of worlds previously considered barren could harbor chemosynthetic life.

Though elusive and shrouded in perpetual darkness, rogue planets are far from insignificant. They are the silent messengers drifting through the interstellar void, carrying vital secrets of the galaxy’s past and illuminating the untapped potential for life in a universe far more diverse and surprising than we once imagined. As our observational technology continues its relentless advance—driven by instruments like the JWST and the upcoming Roman Space Telescope—these wandering worlds will steadily become less mysterious, offering humanity an unprecedented glimpse into the incredible diversity of planetary existence.

FAQs About Rogue Planets: The Lone Wanderers

1. What is a rogue planet?

A rogue planet (also known as a free-floating planet or interstellar planet) is a celestial body with planetary mass that is gravitationally untethered to any star. It drifts alone through the vast expanse of interstellar space, sometimes for billions of years, without the light, warmth, or defined orbital path of a parent star. They are not merely distant exoplanets; they are genuine nomads of the cosmos, following independent trajectories around the galactic center.

2. How do rogue planets form?

Rogue planets primarily form through two distinct mechanisms:

- Ejection from Planetary Systems: This is the most common mechanism. They begin their lives orbiting a star, but during the system’s chaotic early stages, they are gravitationally kicked out (slingshotted) by a close encounter with a more massive object, such as a large gas giant or a passing star. The resulting force accelerates the planet beyond the star’s escape velocity.

- Direct Formation (Born Alone): A smaller number may form independently from the collapse of a small pocket of gas and dust within a molecular cloud. This process is similar to star formation, but the object fails to accumulate sufficient mass to ignite thermonuclear fusion in its core, placing it below the $13$ Jupiter mass ($13 M_J$) threshold that defines a brown dwarf.

3. Can rogue planets support life?

While the surface of a rogue planet is frozen near absolute zero, some may have the potential to harbor life in a unique way. The key is internal heat. Sources like radioactive decay within the planetary core and residual heat from formation could be strong enough to maintain vast subsurface oceans of liquid water beneath a thick, insulating icy crust. Life here would be chemosynthetic, thriving on chemical energy from hydrothermal vents rather than sunlight, challenging our traditional concepts of habitability.

4. How do astronomers detect rogue planets?

Detecting these dark, isolated worlds is extremely challenging. Astronomers rely on indirect, highly sensitive methods:

- Gravitational Microlensing: This is the most successful method. When a rogue planet passes directly between Earth and a distant background star, its gravity momentarily bends and magnifies the star’s light, causing a temporary, measurable brightening.

- Infrared Detection: Young rogue planets (less than a few hundred million years old) retain significant heat from their gravitational formation. This faint thermal glow can be detected in the infrared spectrum by sensitive instruments like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

- Astrometry: Over long periods, highly precise measurements of stellar motions can reveal the subtle, long-term gravitational tug exerted by a nearby, unseen rogue planet, causing a minute “wobble” in the star’s position.

5. How many rogue planets exist in our galaxy?

The estimated number is staggering. Based on current microlensing surveys, rogue planets may outnumber stars in the Milky Way by a significant margin—possibly by a factor of $100$ or more. This means there could be hundreds of billions of such wandering worlds, making them a major component of the galaxy’s mass.

6. Are all rogue planets gas giants?

No. Rogue planets come in a wide variety of sizes and compositions, spanning the full range of planetary types. Scientists believe the population includes small, rocky worlds comparable to Earth or Mars, as well as massive gas giants far larger than Jupiter. The objects ejected from systems are often smaller icy or rocky worlds, as they are easier to fling out.

7. Why are rogue planets important to science?

Studying rogue planets offers profound insights that orbiting planets cannot:

- Planetary Dynamics: They provide hard evidence for the prevalence and efficiency of planetary ejection processes, helping refine models of how star systems are born and the frequency of system instability.

- Galactic Mass Inventory: They help account for a massive, previously unseen component of the galaxy’s baryonic matter, informing models of galactic structure and evolution.

- Astrobiology Expansion: They expand the concept of habitability beyond the Goldilocks Zone, demonstrating the theoretical potential for life to survive on worlds powered solely by internal energy sources.

8. Can we ever visit a rogue planet?

Currently, no. Rogue planets are typically located vast distances away, drifting many light-years from Earth and often moving at high interstellar velocities. While the concept is popular in science fiction, the technology required for interstellar travel and the sheer difficulty of reaching a non-stationary, dark target makes exploration purely theoretical for the foreseeable future. However, future discoveries of a rogue planet passing closer to our own solar system might prioritize it as a long-term target.